‘I made one huge, colossal mistake’

Inside Ottawa’s drug crisis, a woman dealing with homelessness searches for a new life

Thumper walks along a parking median as she looks for potential people to pan handle from in the ByWard Market.

It’s just past 10 p.m. on a cool Saturday night in Ottawa’s ByWard Market. Thumper sits on a narrow metal bar, her thin, underweight body leaning against a narrow black wall that seamlessly blends into the surrounding darkness. A small cup of seasoned off-the-cob corn and a large freshly squeezed lemonade – Thumper’s first meal of the day – rest next to her feet in the dimly lit alleyway. The lingering smell of urine hangs in the air.

The night is young for Thumper, 46, as her routine of panhandling through the often-packed streets of one of Ottawa’s most popular tourist destinations is set to begin.

Donning her small black leather purse – filled with most of her worldly possessions – Thumper takes a few quick bites of her corn and sips from her lemonade, and then lights up the butt of a cigarette as she walks down the alleyway and out into the ByWard Market’s nightlife.

Dodging slow-moving cars, drunk partygoers and eager patrons waiting in line to enter the dozen or so bars and clubs that dot the streets of the Market, Thumper zigzags along a route well established over the nearly two years spent asking passing strangers for spare change or an extra cigarette.

“After being on the streets for 23 months, almost dying three times ... it’s too much for me now.”

Each night that Thumper panhandles, she has two goals. The first: make $11, just enough for a small can of Orange Crush, a corn dog and small portion of fries – layered with ketchup, mayonnaise and vinegar – from Sasha’s Poutine stand, wedged between two lively nightclubs. Her second goal is much more addictive than her near-nightly routine of a 3 a.m. visit to the food stand.

Thumper’s situation is not unique. It’s a symptom familiar to one of Ottawa’s – and Canada’s – most vulnerable populations, a population whose lives intersect with the illicit toxic drug and homelessness crisis, which has claimed the lives of 53,308 people between the start of 2016 and June, 2025, and in 2024 saw nearly 60,000 people experiencing homelessness on any given night across Canada.

Thumper sleeps on a patio couch of a local bar in the courtyard of the ByWard Market

Thumper lays a blanket on top of a couch as she prepares to sleep in the courtyard of the ByWard Market

Thumper kneels on the ground as she looks for dropped spare chance underneath a parked trailer in the ByWard Market

Thumper, left, holds a 20 dollar bill as she panhandles from a patron of a nightlife bar in the ByWard Market

A report by the Association of Municipalities of Ontario from January, 2025, showed that the province “is at a tipping point in its homelessness crisis.”

An estimated 81,515 Ontarians are experiencing “known homelessness,” defined as the number of clients that an organization provides services to – a number that had increased 51 per cent since 2016.

“Without significant intervention,” the group estimates that known homelessness will increase to 294,266 by 2035.

Thumper’s first brush with homelessness didn’t come in Ottawa. It came 26 years earlier when, at the age of 17, she slept on the doorstep of Guelph’s Children’s Aid Society after running away from her physically abusive mother. “My life didn’t get any better from there,” she said.

As Thumper grew up, she chased her dream job of driving long-haul transport trucks across North America, following in the footsteps of her father, and even at times riding alongside him on the open road. But that 18-year-long career came crashing down after a cancer diagnosis forced Ontario’s Ministry of Transportation to pull her licence. “I basically gave up,” she told me. “I didn’t work any more, I had no income, they took my truck.”

Thumper had been sober for 16 years, until one fateful night at a party in her cousin’s Ottawa apartment.

“I made one huge, colossal mistake,” she said, describing the start of a crack-cocaine addiction that has left her with a tidal wave of pain, dead friends and nearly two years of homelessness. “That first high you get off that first rock is what you chase for the rest of the time you’re on it,” explained Thumper, who spent her early days of addiction cooped up with her cousin.

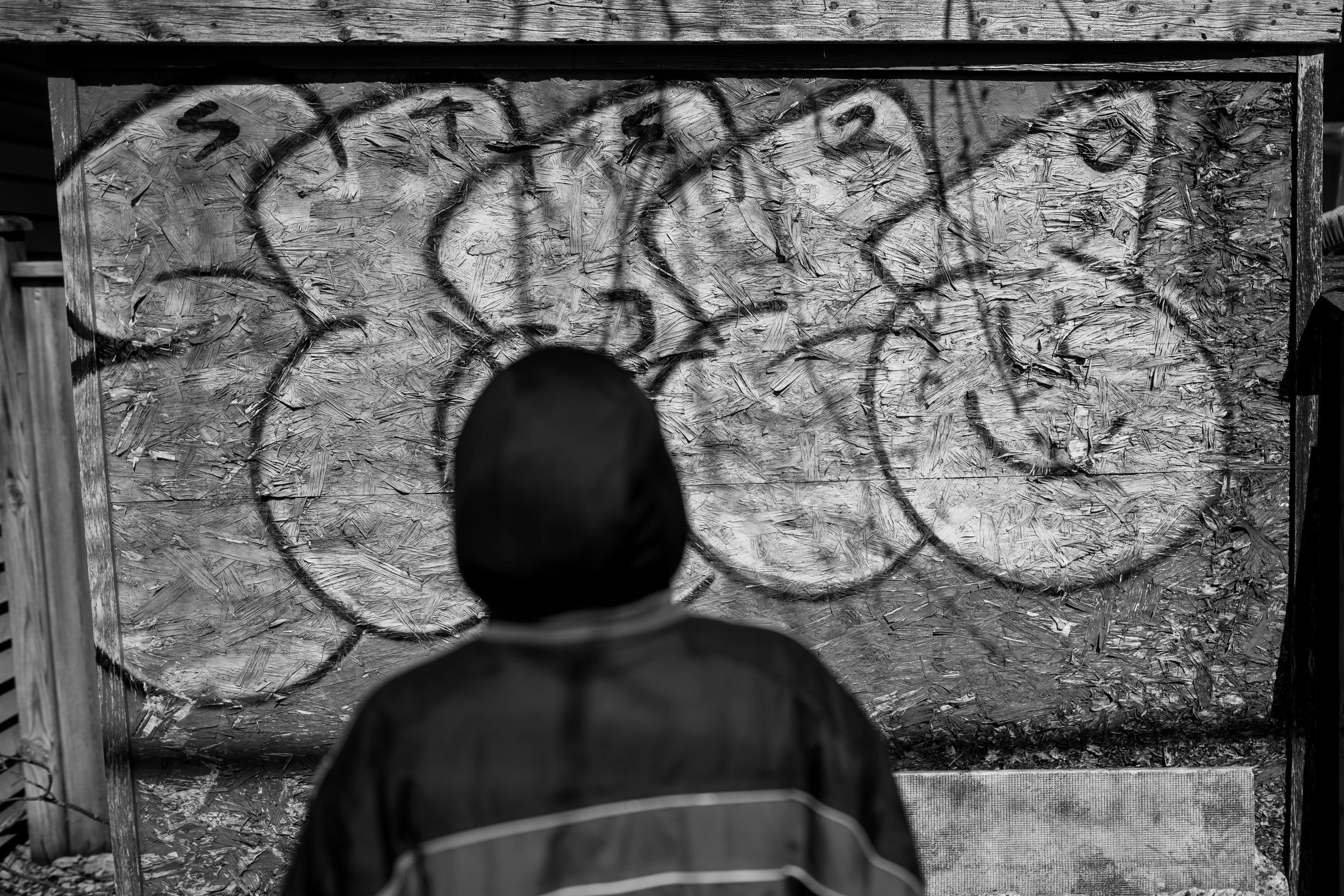

“It was a ‘want’ back then, and then it turned into an ‘I need it’ because it numbs the pain that’s here,” she added, gesturing to her heart. That pain for her came in late 2021 after discovering her cousin, Nicky Halley, dead of a fentanyl overdose in a nearby apartment building. Nicky’s graffiti tag in a back alleyway in Ottawa is the only physical memory Thumper has left of her cousin.

“I wouldn’t let him go. My best friend was gone.”

Thumper looks towards her cousin Nicky ‘Nikko’ Halley’s graffiti tag in the back of an alleyway in Ottawa’s west-end. Nicky - Thumper’s closet friend in the city - died of a fentanyl overdose in October 2021 and his graffiti art is the only physical memory Thumper has left of Nicky.

Thumper’s last resemblance of a normal life disappeared after suffering a home takeover by drug dealers in her basement apartment in Ottawa’s affluent Glebe neighbourhood. Home takeovers involve criminal gangs befriending vulnerable people by using drugs or the threat of violence for control of their home to store or sell drugs from, according to York University’s Homeless Hub.

When she returned in June to retrieve some of her belongings after not living there for over 18 months, she encountered black mould, pests, human and animal feces and urine throughout her one-bedroom unit. Her kitchen table was crowded with discarded intravenous needles, pipes and other opioid-related paraphernalia.

Data from the City of Ottawa shows that 9,390 people slept at least one night in a shelter across the city in 2024 – a 9.1-per-cent increase from 2023. Ottawa’s 2024 Point-in-Time (PiT) count – a one-day survey of a city’s homeless population – showed that of the 2,595 surveyed, 43 per cent reported sleeping in a shelter, 24 per cent were in transitional housing, and 804 respondents reported not sleeping in a shelter over a “reported fear of safety.”

For Thumper, that fear of safety also came with a lack of trust: She claimed that her personal belongings have repeatedly been stolen during months she was in Ottawa’s shelter system. “I can’t trust those girls that are in the shelter [and] I don’t trust the staff,” she told me.

As Thumper battled through the daily struggle of panhandling enough money to pay for a growing addiction and just enough food to stave off starvation, she faced the simultaneous challenge of finding a warm, sheltered – and if lucky, quiet – corner, alleyway or stairwell in the Market to sleep in.

“Unfortunately, I think I’m going to die with a crack stem in my mouth,” she said. While it appears she’s resigned to her fate, she imagines a better life – a place of her own, and a spot in a drug treatment program.

“The first thing I think of when I wake up is: ‘Where is my pipe? I need a toke.’ At home, it’s ‘Where are my smokes?’ I like that better.”

Thumper walks toward Sasha’s Poutine stand on a quiet Monday night. There are no slow-moving cars to dodge, no drunk partygoers and eager patrons waiting in line for the near-empty bars and nightlife clubs that dot her panhandling route – and it’s not her regular 3 a.m. visiting time.

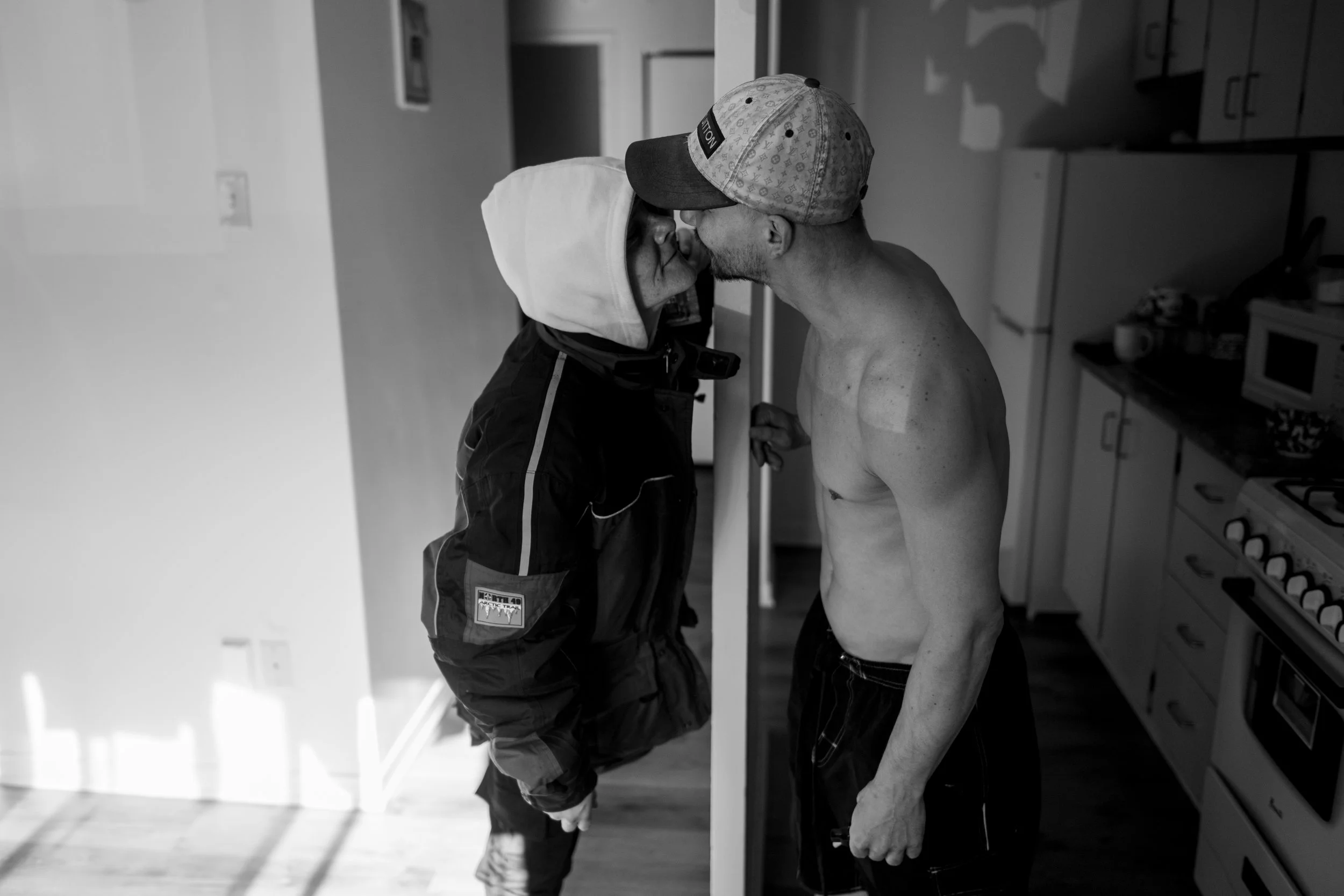

“Tate has been the only person that is 100 per cent on me quitting.”

She places the same order: A small fry, corn dog, an Orange Crush and one extra for the road.

Takeout container and two cans in hand, Thumper walks the streets one last time. She has decided to join her boyfriend, Tate, in Sudbury.

Thumper met Tate, a recovering crack-cocaine user, in early 2025. She would occasionally sleep in his Lowertown neighbourhood apartment before returning to the Market to continue panhandling. After they became estranged, Tate left for Sudbury.

Thumper, left, and Tate share a moment in Tate’s living room apartment building in Lower Town in Ottawa

A note from Thumper to Tate rests on Tate's dining room table in August 2025. The page on the right reads: “Tate I’m so so so sorry. I love you more than my life. I’m stupid. I will do anything to get you back. ANYTHING.”

Thumper stands in the living room of her boyfriend Tate’s apartment building in Lower Town in Ottawa

A wilting flower given to Thumper by Tate rests along a window sill in Tate’s apartment building

It’s minutes to midnight when a lime-green coach bus pulls to a stop in a nondescript shopping centre parking lot in Ottawa’s east end. The pneumatic brakes on the bus hiss and the front door opens.

Thumper frantically collects her life belongings, which are packed into a half-dozen bags, and boards the coach. Minutes later, the doors close.

“I can do this,” she told me before leaving. “I know I can.”

Thumper boards a Flixbus coach bus in Ottawa as it makes it way towards to Sudbury, Ont. on Monday, Sept. 1, 2025